Hoop dancing is one of the many traditions indigenous people are still carrying on today. Originally a healing dance, the art form is now performed at powwows and other cultural events as a form of showmanship. Once a year, it also turns into a competitive sport: This past weekend, the 31st annual World Championship Hoop Dance Contest was held at the Heard Museum in Phoenix. Over its three-decade run, the event has only continued to grow, and this year’s turnout proved bigger than ever. Ninety-seven hoop dancers, from more than three dozen tribes from the U.S. and Canada, turned up to compete, marking a record high number of participants.

While the practice has evolved over the generations, the dancers told Vogue that the spirit behind it has remained the same. “It was originally done as part of a healing ceremony, to help people who are sick or not feeling well mentally or physically,” says Cree dancer James Jones, who traveled from Vancouver to compete at the Heard—his fifth time doing so. “Even though it’s not really done in that practice anymore, it still keeps those good values upheaving.”

Performed by both men and women, the dance involves a solo dancer performing a series of poses and moves with hoops, which are intended to symbolize the circle of life. “You give each one of your hoops this huge respect,” says Violet Duncan, a Plains Cree and Taino dancer who competed alongside her husband, Tony Duncan (Hidatsa/Mandan/Apache), a five-time world champion. “The hoops represent the four directions, the seasons, the stages of life. One hoop talks about our connection that we have with everything.”

At the Heard competition this weekend, hoop dancers were divided into several age categories and performed their sets to two different styles of music: The “northern style” features higher-pitched vocals and slower drumming, while the “southern style” involves lower vocals and faster drumming. Participants were judged on five specific qualities during their five-minute sets: speed, precision, showmanship, timing and rhythm, and creativity. “It’s a tough dance to master,” says Jones. “It’s one thing to do the hoops, but it’s a dance before anything else—you have to really pay attention to the music and do your formations in sync with the drum.”

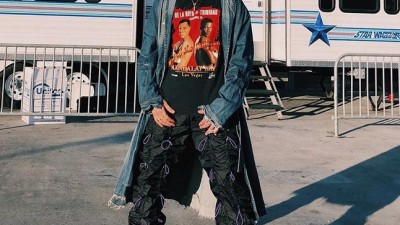

The number of hoops a performer danced with, meanwhile, varied; it depends on style and preference. “It’s not how many hoops you have, it’s what you can do with it,” says Lisa Odjig, an Odawa-Ojibwe dancer who traveled in from Toronto. Traditionally, the hoops were made of red willow but are now made of plastic, wrapped in colored tape to match each performer’s regalia. Indeed, the stunning creations the dancers wore were just as impressive as the dancing itself: Odjig, for one, had been working on her hoop dress, beaded leggings, and moccasins since the spring. “A lot of us make our outfits really nice,” she says. “We take a lot of pride in our work, and it takes a lot of patience, care, and love.”

Tony Duncan says you can learn a whole dancer’s history by what they choose to wear on their back. “It’s a really unique dance that shows the individual qualities and uniqueness about each dancer,” he says. “Different dancers put in moves that are unique to their tribes. Their regalia represents their people.” For Tony and Violet Duncan, the annual Heard competition is also a family affair: The husband-wife duo compete every year along with their four children. “We’ve been teaching the kids hoop dancing just as soon as they could walk,” says Violet. “Every year, unfortunately, our kids are growing. That means new moccasins, new dresses, new beadwork.”

For the family, hoop dancing has been an art form passed down through the generations. “My dad was a hoop dancer. He taught me when I was five years old,” says Tony, while Violet was inspired by watching those in her community. “I learned when I was 12 years old,” she says. “No one in my family was a hoop dancer. Hoop dancing was a specialty dance that you saw very rarely at the powwows. I saw it for the very first time and I was in love with the dance.”

Despite the varied backstories and tribes, a common thread with all of this weekend’s performers was a sense of carrying on a time-honored tradition—one that continues to holds much significance, both to those performing and watching. “Dancing to the beat of the drum is good medicine,” says Odjig. “When we’re out there dancing, we’re not dancing for ourselves. We’re dancing and praying for everyone that’s watching. It’s important to keep this dance strong and alive and pass it on from generation to generation. It’s a part of our history.”

Photos: Courtesy of Heard Museum

Original article: https://www.vogue.com/vogueworld/article/heard-museum-hoop-dancing-championship-contest-photos

Comments